Tagged: Highlanders

Missing #4- Kid Elberfeld

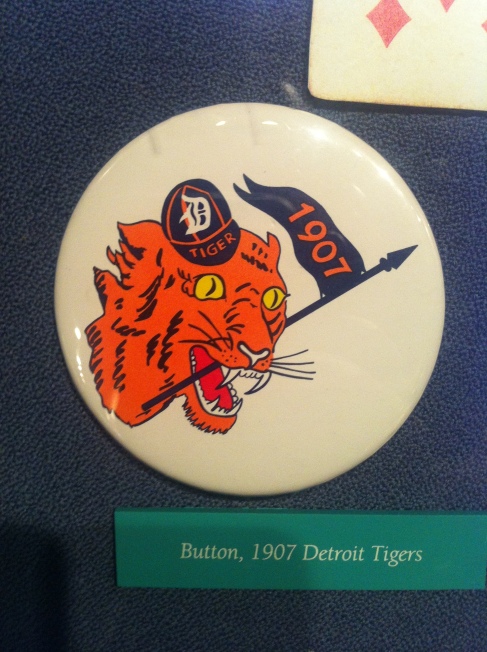

You can dedicate your life to baseball and have a dramatic impact on people and the game. However, this does not mean you are destined for Cooperstown. Norman Arthur Elberfeld grew up in Cincinnati, cheering for the Reds and made a name for himself on local diamonds. The Tabasco Kid, or Kid, played primarily Shortstop for 14 seasons with six teams: Philadelphia Phillies (1898), Cincinnati Reds (1899), Detroit Tigers (1901-1903), New York Highlanders (1903-1909), Washington Nationals (1910-1911), and Brooklyn Dodgers (1914). He spent the 1908 season as the Player-Manager for the New York Highlanders, guiding them to a 27-71 record, .276 WL%. Elberfeld was a much better Major League player than manager.

Elberfeld appeared on the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot. This came after a career in which he played in 1,292 Games, scored 647 Runs, collected 1,235 Hits, including 169 Doubles, 56 Triples, 10 Home Runs, 535 RBI, 213 Stolen Bases, drew 427 Walks, 166 Strikeouts, posted a .271 BA, .355 OBP, .339 SLG, .694 OPS, and 106 OPS+. Elberfeld turned Hit By the Pitch into an art form. His 165 Hit By Pitches still ranks 19th all time.

Defensively, Elberfeld played in 1,265 Games, made 1,196 Starts, 1,135 Complete Games, 10,835 Innings, had 6,993 Chances, made 2,681 Putouts, with 3,774 Assists, committed 538 Errors, .923 FLD%, 5.36 RF/9, and 5.10 RF/G. He was fearless, never shying away from confrontation. Elberfeld wore a whalebone shin guard after being spiked multiple times while turning Double Plays. His aggression towards opposing players and umpires, leading to multiple injuries, fights, and suspensions.

The best season of Elberfeld’s career came with the 1901 Detroit Tigers. He played in 121 Games, scored 76 Runs, collected 133 Hits, including 21 Doubles, 11 Triples, 3 Home Runs, 76 RBI, 23 Stolen Bases, drew 57 Walks, 18 Strikeouts, with a .308 BA, .397 OBP, .428 SLG, .825 OPS, and 125 OPS+. Elberfeld posted career bests in Triples, Home Runs, RBI, BA, SLG, and OPS. Despite the great start, Elberfeld failed to build a Hall of Fame career.

The game continues to change so it is only appropriate to compare Elberfeld to his contemporaries who were elected to Cooperstown. There are 26 Hall of Fame Shortstops, of which six played during the Dead Ball Era. The average Dead Ball Era Shortstop played 19 seasons, 2,078 career Games, scored 1,253 Runs, collected 2,286 Hits, including 369 Doubles, 143 Triples, 47 Home Runs, 1,131 RBI, 463 Stolen Bases, drew 633 Walks, 499 Strikeouts, with a .290 BA, .350 OBP, .388 SLG, .738 OPS, 113 OPS+, and 69.4 WAR. These Shortstops played their way into the Hall of Fame. Kid Elberfeld did not. He was only better by having 333 fewer Strikeouts and a .005 higher OBP. It is not a close comparison.

Kid Elberfeld was a true baseball man, spending time as a coach, scout, mentor, and teacher. He was good for the game, but not a Hall of Famer. On the 1936 ballot, Elberfeld received 1 vote, 0.4%. He was tied for the 39th most votes on the ballot. He would appear on the Hall of Fame ballot five times, peaking with 0.8% in both 1938 and 1945. The Hall of Fame voters got it right. Kid Elberfeld does not deserve to be enshrined in Cooperstown. Sometimes the value of an honor is shown through those not receiving it.

DJ

Missing #3- Lou Criger

Sometimes life is not what you know, but who you know. This may explain Lou Criger’s name on the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot. His numbers did not justify his appearing before the voters for Cooperstown. The most likely reason he was on the ballot was his close relationship with Cy Young. Criger, like many players, did not play well enough to be considered for enshrinement, yet somehow he was on the 1936 ballot and received seven votes.

Lou Criger played for 16 seasons with five teams: Cleveland Spiders (1896-1898), St. Louis Cardinals (1899-1900), Boston Americans/ Red Sox (1901-1908), St. Louis Browns (1909, 1912), and New York Highlanders (1910). He played in 1,012 career Games, scored 337 Runs, collected 709 Hits, including 86 Doubles, 50 Triples, 11 Home Runs, 342 RBI, 58 Stolen Bases, drew 309 Walks, 225 Strikeouts, with a .221 BA, .295 OBP, .290 SLG, .584 OPS, and 72 OPS+. Criger was all glove and no bat. He caught 984 Games, with 692 Starts, 625 Complete Games, 8,396 Innings, he had 5,866 Chances, made 4,354 Putouts, 1,342 Assists, committed 170 Errors, and turned 102 Double Plays. His career .971 FLD% was .008% higher than league average, his 6.11 RF/9 was 0.39 higher, his 5.79 RF/G was 0.13 higher, he allowed 120 Passed Balls, 934 Stolen Bases, with 937 Caught Stealing, a 50% CS% which was 6% higher than league average. Criger used his strong and accurate arm to dictate the running game of the opposing team like no other catcher in the early years of baseball.

The tough, but slender Criger had his best season with the 1898 Cleveland Spiders. He played in 84 Games, scored 43 Runs, collected 80 Hits, including 13 Doubles, 4 Triples, 1 Home Run, 32 RBI, 2 Stolen Bases, drew 40 Walks, 22 Strikeouts, with a .279 BA, .377 OBP, .362 SLG, .739 OPS, and 115 OPS+. He set career bests in Runs, Hits, BA, OBP, SLG, OPS, and OPS+. It was a banner year for an otherwise offensively inept player.

Criger did not waste his one appearance in the World Series. Playing with the Boston Americans in the first World Series, he appeared in all 8 Games, scored 1 Run, collected 6 Hits, 4 RBI, drew 2 Walks, 3 Strikeouts, with a .231 BA, .286 OBP, .231 SLG, and .516 OPS. Criger and the Americans won the series five games to three.

Criger was Cy Young’s preferred Catcher, and their relationship was fruitful. They played 12 seasons together from 1896 to 1908 with the Cleveland Spiders, St. Louis Cardinals, and Boston Americans/ Red Sox. In the 9 seasons after Criger became a full time Catcher, 1897 to 1908, Young posted a 229-131 record, with a 2.38 ERA, 1.056 WHIP, and 146 ERA+. Criger caught Young’s Perfect Game on May 5, 1904. However when Criger caught just two Games in 1906, Young posted a 13-21 record, 3.19 ERA, 1.088 WHIP, and 86 ERA+. It was the worst season of Young’s Hall of Fame career. He led the American League in Losses, did not throw a Shutout, and had his fewest Complete Games and Innings Pitched of any season when he made 20 Starts. A healthy Criger’s return for 1907 and 1908 led Young back to a 42-26 record, 1.65 ERA, 0.940 WHIP, and 152 ERA+. Criger also caught Young’s No Hitter on June 30, 1908. The comfort of a familiar catcher does a lot for a pitcher’s success.

While Criger was critical to Young’s Hall of Fame career, it does not make him a Hall of Famer. Reaching Cooperstown places a player in elite company. There are only 19 Catchers in the Hall of Fame, and only three played during the Deadball era: Buck Ewing, Roger Bresnahan, and Ray Schalk. These three Hall of Famers averaged 18 seasons, 1,508 Games played, 797 Runs scored, 1,407 Hits, 222 Doubles, 99 Triples, 36 Home Runs, 669 RBI, 248 Stolen Bases, 581 Walks, 352 Strikeouts, .278 BA, .359 OBP, .383 SLG, .742 OPS, and 113 OPS+. The comparison between these legends and Criger is not realistic. Criger has 2.2 more dWAR and 127 fewer Strikeouts, everything else is not close.

Lou Criger received the third highest vote total of any player not enshrined into the Hall of Fame from the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot. His seven votes, 3.1%, were the 29th highest of any candidate. Criger remained on the Hall of Fame ballot for four years, peaking with 8.0% in 1937. There is no amount of smoke and mirrors to justify his induction into Cooperstown. The real question is how did he get on the ballot to begin with? Was his inclusion due to his relationship with Cy Young or was it the work of the good ole boys club? Either way it is a travesty.

DJ

Missing #1- Hal Chase

The first player from the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot missing from Cooperstown is First Baseman Hal Chase. The Los Gatos, California native attended Santa Clara University before embarking on a 15 season Major League career. Chase played for 5 teams: New York Highlanders/Yankees (1905-1913), Chicago White Sox (1913-1914), Buffalo Buffeds/Blues (Federal League) (1914-1915), Cincinnati Reds (1916-1918), and New York Giants (1919). He played in 1,919 career Games, scored 980 Runs, collected 2,158 Hits, including 322 Doubles, 124 Triples, 57 Home Runs, 941 RBI, 363 Stolen Bases, drew 276 Walks, 660 Strikeouts, posted a .291 BA, .319 OBP, .391 SLG, .710 OPS, 112 OPS+, and 23.0 WAR. Chase won the 1916 National League Batting Title with the Reds.

On the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot, Chase received 11 votes, 4.9%, falling well short of the 226 necessary for induction. He returned on the 1937 Hall of Fame ballot before falling off. Why did he never reach Cooperstown? There are 26 First Basemen in the Hall of Fame. Why not 27?

What does the average Hall of Fame First Baseman look like? They played 18 Seasons, 2,075 career Games, scored 1,289 Runs, collected 2,321 Hits, including 404 Doubles, 99 Triples, 223 Home Runs, 1,201 RBI, 213 Stolen Bases, drew 881 Walks, 755 Strikeouts, with a .303 BA, .377 OBP, .468 SLG, .845 OPS, and 60.6 WAR. Chase ranks above average in only three categories: At Bats, Triples, and Stolen Bases. He had 191 more At Bats than the average Hall of Fame First Baseman, roughly half a season. Chase also hit 25 more Triples and Stole 239 more Bases. Everything else is below average.

These numbers are unfair to Chase as the game has changed in the century since he last played. First Basemen are now expected to hit for power and drive in runs, not steal bases and leg out Triples. A more fair comparison for Chase is against his contemporaries, the seven Hall of Fame First Basemen who played all or the majority of their careers in the Dead Ball Era. These seven are: Cap Anson, Roger Connor, Dan Brouthers, George Sisler, Jake Beckley, France Chance, and George Kelly. On average they played 19 Seasons, 1,936 career Games, scored 1,379 Runs, collected 2,430 Hits, including 417 Doubles, 163 Triples, 100 Home Runs, 1,296 RBI, 277 Stolen Bases, drew 694 Walks, 413 Strikeouts, with a .319 BA, .384 OBP, .458 SLG, .842 OPS, and WAR 63.8. Against his contemporaries Chase is only above average in Stolen Bases, with 86 more Steals. The First Basemen of the Live Ball Era make Chase look slightly better, but neither comparison helps his Hall of Fame candidacy.

The focus is on Chase’s skills with the bat, because he was bad with the glove. His -15.3 dWAR would rank 7th worst among Hall of Fame First Basemen. The six worse than him played in the Live Ball Era, with only Jim Bottomley playing before integration. First Basemen today are paid for their power, not their glove.

Perhaps it is not fair to only compare Chase to Hall of Fame First Basemen, due to the changes baseball has undergone since he played. Does he compare well against all Hall of Fame position players? No. He played 3 fewer seasons, appeared in 115 fewer games, scored 281 fewer runs, collected 115 fewer Hits, including 72 fewer Doubles, he did hit 25 more Triples, but also 160 fewer Home Runs, 235 fewer RBI, he Stole 157 more Bases, drew 584 fewer Walks, had 75 fewer Strikeouts, posted a .013 lower BA, .059 lower OBP, .079 lower SLG, .138 lower OPS, 18 5less OPS+, and 40.5 less WAR. The argument takes a further hit when the Hall of Famers who played their entire careers in the Negro Leagues are excluded. The Hall of Fame players from the Negro Leagues have incomplete statistical records. Removing their numbers only weakens Chase’s case for the Hall of Fame.

Even accounting for the change in the position it is difficult to argue that Chase was ever a legitimate Hall of Fame candidate. His exclusion from Cooperstown is not a failure by the Hall of Fame voters. While Chase finished with the 25th most votes out of the 50 candidates on the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot there is little evidence his career made him a Hall of Famer. The numbers are clear, if he were alive today he would need to buy a ticket like the rest of us to enter Cooperstown.

DJ

Error of Their Ways

Putting the ball in play puts pressure on the defense. A fielder can drop a fly ball, boot a grounder, or throw the ball away. Even the most routine play is not automatic. However, are all Errors bad? Are they the mark of a poor defender? Could they be a sign of a good defender?

Herman Long holds the record for most career Errors, 1,096. The logical assumption is he was a terrible defender. However, there is a reason he played 16 seasons in the Major Leagues. Long played Shortstop from 1889 to 1904 for the Kansas City Cowboys, Boston Beaneaters, New York Highlanders, Detroit Tigers, and Philadelphia Phillies posting a 16.8 dWAR, 83rd highest all time. In 11,881 Chances, he made 4,450 Putouts with 6,335 Assists, and turned 785 Double Plays. Long had a career .908 Fielding % (Fld%), 5.86 Range Factor per 9 Innings (RF9), and a 5.73 Range Factor per Game (RFG). Range Factor is the number of plays a player is involved in per game or per 9 innings. It is especially useful when comparing players from the same era. Herman Long’s contemporaries at Shortstops posted a .904 Fld%, 5.67 lgRF9, and 5.50 lgRFG. Long was better by .004 Fld%, 0.19 RF9, and 0.23 RFG. These differences are a few plays over a long season, but they can alter a tight pennant race.

Herman Long received just one Hall of Fame vote, others have entered team hall of fames or Cooperstown due to their skill with the glove. The Human Vacuum, the Wizard, and the Blade are among the best defensive infielders ever. Brooks Robinson spent his entire 23 season career in Baltimore stationed at third base for the Orioles. The Human Vacuum committed 264 Errors, compiled the third highest career dWAR, 39.1, and won 16 Gold Gloves. Robinson was an institution at the hot corner. In 9,196 Chances, he made 2,712 Putouts with 6,220 Assists, and turned 621 Double Plays. He had a career .971 Fld%, 3.20 RF9, 3.08 RFG, and 293 Total Zone Total Fielding (Rtot). Rtot is the number of runs above or below average a player is worth based on the number of plays made. The other third basemen of Robinson’s era had a .953 Fld%, 3.09 lgRF9, and 3.10 lgRFG. Robinson surpassed his contemporaries by .018 Fld% and 0.11 RF9, but had a -0.02 RFG.

Ozzie Smith is possibly the greatest defensive Shortstop in baseball history. He won 13 Gold Gloves while creating the highest dWAR ever, 44.2. During the Wizard’s 19 season career, he had 12,905 Chances, made 4,249 Putouts with 8,375 Assists, turned 1,590 Double Plays, and committed 281 Errors, 285th most all time. It is easy to assert a player’s greatest, but do the numbers back up your opinion. Smith had a career .978 Fld%, 5.22 RF9, 5.03 RFG, and 239 Rtot. The other Shortstops had a .966 lgFld%, 4.78 lgRF9, and 4.77 lgRFG. Smith outpaced his contemporaries by .022 Fld%, 0.44 RF9, and 0.26 RFG. The Wizard of Oz was more than backflips. If he could not make a play it was probably impossible.

Less heralded than Robinson and Smith, Mark Belanger was a defensive master. He won 8 Gold Gloves and his 39.5 dWAR is second behind Ozzie Smith. In 18 seasons, Belanger had 9,082 Chances, made 3,040 Putouts with 5,831 Assists, and turned 1,061 Double Plays, against just 211 Errors. His defensive excellence ranks him outside the top 400 in career Errors. Belanger’s career .977 Fld%, 5.16 RF9, 4.50 RFG, and 241 Rtot far outpaced his competition. Other Shortstops had a .964 Fld%, 4.93 lgRF9, and 4.92 lgRFG. The Blade was better, .013 Fld%, 0.23 RF9, and -0.43 RFG. Belanger’s long and productive career with the glove did not however take him to Cooperstown like Robinson and Smith, receiving 3.7% of the vote in 1988, his only year on the ballot.

Baseball teams rely on their defense to make routine plays every time and incredible plays whenever possible. Players do occasionally boot routine plays or try to do too much. Baseball history is littered with examples. Currently Starlin Castro and Elvis Andrus are locked in a fight for most Errors among active players. Both have quietly built strong careers, but have taken different paths to this point.

Elvis Andrus arrived in Texas as part of the Mark Teixeira trade with Atlanta. In 12 seasons with the Rangers, Andrus has had 7,210 Chances, made 2,529 Putouts with 4,487 Assists, turned 1,064 Double Plays, and committed 194 Errors. He has a career .973 Fld%, 4.47 RF9, 4.31 RFG, and 52 Rtot. Other Shortstops have a .973 Fld%, 4.17 lgRF9, and 4.14 lgRFG. The Fld% is identical, but Andrus has a higher RF9 and RFG, 0.30 and 0.17 respectively. This greater Range has produced a 10.7 dWAR, 211th all time. Elvis Andrus has helped Texas defensively by creating more Chances and thus more outs.

Starlin Castro broke in with the Chicago Cubs as a 20 year old, playing 123 games his first season. He has played 11 seasons for the Cubs, Yankees, Marlins, and Nationals. Castro has not enjoyed the same defensive success as Elvis Andrus as they approach 200 career Errors. In 6,170 Chances, Castro has 2,197 Putouts with 3,778 Assists, turned 757 Double Plays, and committed 195 Errors. He has career .968 Fld%, 4.22 RF9, 4.05 RFG, and -32 Rtot. Compared to his contemporaries at Short and Second, Castro has not fared well against their .976 Fld%, 4.29 lgRF9, and 4.26 lgRFG. He is behind in all three measurements, -.008 Fld%, -0.07 RF9, and -0.04 RFG. Castro transitioned from Shortstop to Second Base after spending roughly 60% of his career games at Short. The move to Second has hidden some of his lack of range. However, Castro is barely an above defender, posting a 1.2 career dWAR. His first four seasons in the Majors saw him commit 27, 29, 27, and 22 Errors. While Castro has improved, at best he is league average.

Fielding statistics are not simply counting Errors. Fielding must be compared against other players from the same era. Baseball Reference lists the top 500 single seasons for Errors. Only 14 of the top 500 seasons occurred since 1920, and none since 1941. Resting atop this dubious leaderboard are Herman Long (1889) and Billy Shindle (1890), each committing 122 Errors.

In 1889, Long set the record with 122 Errors. He had 983 Chances, made 355 Putouts with 506 Assists, and turned 59 Double Plays. Despite his apparent struggles, Long was an above average Shortstop. He had a .874 Fld%, 6.60 RF9, and 6.36 RFG against the league’s .873 Fld%, 5.32 lgRF9, and 5.13 lgRFG. Long had a .001 Fld%, 1.28 RF9, and 1.23 RFG advantage. Long, like Andrus, made plays at a league average rate but created more Chances due to his greater Range. The following season Billy Shindle also committed 122 Errors. He had 834 Chances, made 268 Putouts with 444 Assists while turning 67 Double Plays. Shindle posted a .862 Fld%, 5.62 RF9, and 5.45 RFG, whereas his opponents posted a .868 Fld%, 5.27 lgRF9, and 5.13 lgRFG. Shindle converted Chances into outs below the league average, -.006 Fld%, but he fielded more balls in play, 0.35 RF9 and 0.32 RFG. Creating Chances improves a team’s likelihood of winning by limiting their opponent’s scoring opportunities.

Players can commit Errors on Chances that others watch go by for hits. Simply counting Errors does not provide a complete picture of a player’s defensive abilities. Their Range is equally important to their Fielding %. Players must field a ball before they can convert Chances into outs. Errors can happen from bad bounces or throws, but the real value of a defender is can they create more Chances and outs in support of their pitcher and team. Errors are part of baseball, but they are not entirely bad, there is more than meets the eye.

DJ

Hall of Famer of the Week- Ty Cobb

Born on September 11, 1886 in Narrows, Georgia, Ty Cobb would become one of the greatest players in baseball history. During his 24 year playing career, 22 with the Detroit Tigers and two with the Philadelphia Athletics, Cobb hit over .300 23 times. His rookie year in 1905, Cobb hit .240 in 150 at bats, however he would never hit below .316 (his second season) again for the rest of his career. His .367 career batting average remains a Major League record, which is unlikely to be surpassed. He hit over .400 three times during his career (1911-.420, 1912-.409, and 1922-.401). Remarkably Cobb did not win the batting title in 1922, as George Sisler hit .420 for the St. Louis Browns. In 1909, Cobb won the Triple Crown leading the American League with a .377 batting average, 9 home runs, and 107 RBI. The 1911 season was one of Cobb’s best seasons, and arguably one of the greatest of all time. Cobb hit .420, collected 248 hits, 47 doubles, 24 triples, 127 RBI, scored 147 runs, 83 stolen bases, SLG .621, and OPS 1.088; all of which led the American League. Cobb’s efforts earned him the Chalmers Award, the precursor to the MVP.

The legendary tales of Cobb sharpening his spikes to intimidate others shows how intense of a competitor Cobb was on the field. Cobb knew the strike zone as well as any hitter to have ever played the game. He had only 680 strikeouts during his career, striking out over 50 times in a season only once. His incredible plate discipline along with his speed on the base path presented a major problem to opposing teams. Cobb was almost sure to make contact with any pitch, which made the hit and run play possible any time a runner was on base. If the defense tried to prevent the runner from advancing, Cobb could hit the ball to foil the defenses plans. Once he was on base, Cobb could distract the pitcher from the hitter. Few, if any, infielders wanted to get in his way as he advanced around the bases for fear of injury from his spikes. Cobb had 898 stolen bases during his career. It was nearly impossible to keep Cobb off the bases and once he was there between his speed and intelligence opponents were unlikely to get him out.

Cobb’s fierce nature on the field was unsurpassed during his playing career, most notably with his high spikes. However, Cobb’s intensity extended beyond the field, as in 1912 he went into the stands in New York while playing the Highlanders and beat a man after the fan hurled insults at Cobb during a game.

Away from the baseball field Cobb was a shrewd investor, investing heavily in Coca Cola during its early years. He was also a generous man, and his generosity off the field continues to be felt today. Cobb founded the Ty Cobb Educational foundation, which has helped thousands of Georgia students to attend college by awarding scholarships. To date, more than thirteen million dollars have been awarded to students. Cobb also established the Cobb Memorial Hospital in 1950. This hospital has become the Ty Cobb Healthcare System which continues to serve rural areas of Northwest Georgia.

Cobb was a member of the inaugural class inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936. He received 222 out of 226 votes. He received more votes than the other members of the 1936 class: Honus Wagner (215), Babe Ruth (215), Christy Mathewson (205), and Walter Johnson (189). Cobb earned the honor of being the first inductee into the Baseball Hall of Fame. This honor was bestowed upon him as he received the highest vote total among those in the first class in 1936. Cobb’s 98.23% of the Voting for the Hall of Fame remains the fourth best all time, behind only Tom Seaver (98.84%), Nolan Ryan (98.79%), and Cal Ripken Jr. (98.53%).

D