Tagged: Honus Wagner

Bucky: A Story of Baseball in the Deadball Era

Baseball is well covered in literature. The obsession with America’s Pastime has produced many great books. Bucky: A Story of Baseball in the Deadball Era by Fred Veil is no exception. The book is a work of fiction that uses the available historical record to follow Fred “Bucky” Veil through his professional baseball career.

Bucky Veil found his way to the Major Leagues like many players in the early years of baseball, through skill and luck. Veil was skilled at getting batters out. Pitching for local teams his abilities were undeniable. He began moving up from local leagues to bigger and bigger leagues until the Pittsburgh Pirates signed him.

The Pirates were coming off a dominant 1902 season in which they easily won the National League Pennant. Early in the season, Bucky felt like he did not belong among these great players. However, like most Rookies, this began to change the better he played. In 1903, Veil pitched in 12 Games, Made 6 Starts, Finished 6 Games, threw 4 Complete Games, with 70.2 Innings Pitched, 35 Runs allowed, 30 Earned Runs, 1 Home Run, 36 Walks, 20 Strikeouts, against 298 Batters Faced, while posting a 5-3 Record, 3.82 ERA, and 1.500 WHIP. Bucky made 1 Start between May 31 and August 2 due to illness. It looked like he was beginning a great career.

Unfortunately, Malaria derailed Bucky’s career. Veil pitched in only one Major League game in 1904. Bad luck hinders many careers. After a year off the mound, Veil returned to pitch for the 1905 and 1906 Columbus Senators of the American Association. He did well, but his time in the Major Leagues was over.

The story of Bucky Veil’s baseball career is presented in an unique way. Fred Veil writes about his grandfather’s baseball career. This familiar connection allows for a closer connection regarding Veil’s personal life away from the diamond. The humanizing of Veil as he meets and marries his wife and begins his life away from his hometown helps connect readers with the players. We face many of the same challenges, but ballplayers do it under an ever increasing microscope.

Fred Veil mixes in accurate information with a fictionalized account of his grandfather’s life, including Bucky’s interactions with future Hall of Famers Honus Wagner, Fred Clarke, and Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss. This blending of fact and fiction create an entertaining story about a player that could easily be lost to history. Readers can simply enjoy the story and fully immerse themselves in this baseball book that is written like so few others.

Bucky: A Story of Baseball in the Deadball Era by Fred Veil is an entertaining read. It helps baseball readers who may not venture into the fiction section very often, expand their literary horizons. Fred Veil has written an excellent book, for which his grandfather would be proud. Fred Veil gives baseball readers something new to enjoy. Bucky: A Story of Baseball in the Deadball Era earns a 7 out of 10, a Triple.

DJ

The Missing 7

The weather is warming up. The Major League season is well underway and some teams are already separating themselves from the rest of the league. The slow, sad season-long train wreck in Oakland has begun. We are less than three months away from the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony for the Class of 2023.

The four members of the Class of 2023 are:

- Scott Rolen, BBWAA

- Fred McGriff, Contemporary Baseball Era Committee

- Pat Hughes, Ford C. Frick Award

- John Lowe, BBWAA Career Excellence Award

It has been 88 years since the first Hall of Fame Class. The First Five: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson. No Hall of Fame class will ever rival the Class of 1936, it is unfair to even compare. Examining the 1936 ballot, the voters had a difficult task. They had to select the most deserving candidates from a list of 50 players.

Over time Hall of Fame voters have elected 42 of the 50 players on the 1936 ballot. Countless books and articles have been written about these 42 players, but what about the eight not in Cooperstown. They were good enough to be on the ballot, but why were they never deemed worthy of induction?

The reason why for one of the eight is obvious. Shoeless Joe Jackson received 0.9% of the vote, 2 votes. He was banned from baseball by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis following the 1919 Black Sox scandal. There is plenty of debate about Jackson’s involvement and if it is time to welcome him back into baseball. That debate is for another day. This leaves seven players out of the Hall of Fame.

The seven players from the 1936 Hall of Fame ballot missing from Cooperstown are:

Why are these seven players not in Cooperstown? Are they the exceptions or were all worthy players inducted? How do they compare to the others on the ballot, and all Hall of Famers? Are they unjustly left out or were some players erroneously elected. The Hall of Fame cannot welcome every player. If it did, the honor would become meaningless. There is constant debate about who should and should not be in Cooperstown. Many of the debated players fall at the intersection of the Hall of Fame and the Hall of Very Good. It is difficult to determine exactly where the divide rests. This raises the question, is it better to exclude a worthy Hall of Famer to ensure no unworthy player enters Cooperstown or is it better to ensure every Hall of Fame player is inducted even if a few unworthy players sneak in? This is the central question of who is and is not a Hall of Famer.

DJ

United States of Baseball- Pennsylvania

In the early days of baseball the majority of players were drawn from the eastern United States. Pennsylvania was an early hotbed for baseball. The Keystone State has sent 1,481 players to the Majors, the second most productive state behind only California. The Keystone State continues to produce players every year. The greatest pitcher born in Pennsylvania is Christy Mathewson. His 99.81 career WAR is the 9th highest of pitching state and territory leaders. The greatest position player born in the Keystone State is Honus Wagner. His 130.82 career WAR ranks 6th among position player leaders. Pennsylvania has a combined 230.63 WAR, ranking the Keystone State 5th in the United States of Baseball.

Few pitchers were as well respected by their peers and subsequent generations as Christy Mathewson. The Factoryville native played 17 seasons with two teams: New York Giants (1900-1916) and Cincinnati Reds (1916). The Right-Hander pitched in 636 career Games, made 552 Starts, 73 Games Finished, threw 435 Complete Games, including 79 Shutouts, posted a 373-188 record, with 4,788.2 Innings Pitched, allowed 4,219 Hits, 1,620 Runs Scored, 1,135 Earned Runs, 89 Home Runs, 848 Walks, 2,507 Strikeouts, 2.13 ERA, 1.058 WHIP, and 136 ERA+.

Mathewson left little doubt as to why he was a member of the original Hall of Fame class in 1936. Mathewson won the Pitching Triple Crown twice. He won the National League ERA title five times. He pitched four seasons with a WHIP below 1.000 and five seasons with an ERA below 2.00. Mathewson was in control when he was on the mound, pitching over 300 Innings 11 times, winning 20 games 13 times, and 30 games four times. There was little he could not do with a baseball.

Deciding which season of Mathewson’s Hall of Fame career was the best is problematic. Perhaps 1908 with the Giants was his best. Mathewson appeared in 56 Games, made 44 Starts, Finished 9 Games, threw 34 Complete Games, including 11 Shutouts, posted a 37-11 record, in 390.2 Innings Pitched, allowed 281 Hits, 85 Runs, 62 Earned Runs, 5 Home Runs, 42 Walks, 259 Strikeouts, 1.43 ERA, 0.827 WHIP, and 259 ERA+. His dominance led the National League in Games, Games Started, Complete Games, Shutouts, Innings Pitched, Hits allowed, Batters Faced, Wins, ERA, WHIP, and ERA+. Despite his efforts the 98 win Giants finished one game behind the Chicago Cubs for the National League Pennant.

The New York Giants were a force with Mathewson on the mound. They appeared in four World Series, winning in 1905 before losing in 1911, 1912, and 1913. In his four Fall Classics, Mathewson pitched in 11 Games, made 11 Starts, threw 10 Complete Games, including 4 Shutouts, posted a 5-5 record, with 101.2 Innings Pitched, allowed 75 Hits, 22 Runs, 11 Earned Runs, 1 Home Run, 10 Walks, 48 Strikeouts, 0.97 ERA, and 0.836 WHIP. Despite pitching some of his baseball, Mathewson found little success in the World Series.

The Original Hall of Fame class had more than one Pennsylvanian. Honus Wagner was also among the first five players chosen for Cooperstown. Johannes “Honus” Wagner was born in Chartiers, Pennsylvania. The Flying Dutchman played his entire 21 season career with the Pittsburgh Pirates (1897-1917). The Hall of Fame Shortstop played in 2,794 career Games, scored 1,739 Runs, collected 3,420 Hits, 643 Doubles, 252 Triples, 101 Home Runs, 1,732 RBI, 723 Stolen Bases, drew 963 Walks, 735 Strikeouts, with a .328 BA, .391 OBP, .467 SLG, .862 OPS, and 151 OPS+.

Wagner struck fear in the hearts of pitchers every time he stepped to the plate. The Flying Dutchman scored 100 Runs seven times, had eight straight seasons with 40 Stolen Bases, and nine seasons with 100 RBI. Wagner hit .300 for 15 consecutive seasons. He won eight National League Batting titles, including seven in nine seasons. His ferocity with the bat allowed him to lead the National League in Doubles seven times and Triples three times. Even in the field, Wagner was a great player. The Pirates Shortstop played in 1,887 Games, 16,786 Innings, had 11,293 Chances, made 4,576 Putouts, with 6,041 Assists, and committed 676 Errors. Wagner posted a career .940 FLD%, well above the .927 league average. His range also allowed him to reach more balls than other Shortstops. Wagner’s 5.69 RF/9 was better than the 5.43 league average, so too was his 5.63 RF/G against the 5.36 league average. Wagner was great all over the diamond.

The best season of Honus Wagner’s career came with the 1908 Pirates. He played in 151 Games, scored 100 Runs, collected 201 Hits, including 39 Doubles, 19 Triples, 10 Home Runs, 109 RBI, 53 Stolen Bases, drew 54 Walks, 22 Strikeouts, posting a .354 BA, .415 OBP, .542 SLG, .957 OPS, and 205 OPS+. Wagner led the National League in Hits, Doubles, Triples, RBI, Stolen Bases, Batting Average, On-Base Percentage, SLG, OPS, OPS+, and Total Bases. He set career highs in OPS+ and Total Bases, while tying his career high in Hits and Home Runs. It was a year of domination in a dominant career.

Wagner and the Pirates reached the World Series twice. They lost in 1903, before winning in 1909. He played in 15 World Series Games, scored 6 Runs, collected 14 Hits, including 3 Doubles, 1 Triple, 9 RBI, with 9 Stolen Bases, 7 Walks, 6 Strikeouts, .275 BA, .393 OBP, .373 SLG, and .766 OPS. Wagner’s greatest helped bring a championship to western Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania has a long baseball history. The Keystone State is the birthplace of 25 Hall of Famers, the third most of any state behind only New York and California. The Pennsylvanians enshrined in Cooperstown are: Roy Campanella, Nestor Chylak (Umpire), Stan Coveleski, Nellie Fox, Ken Griffey Jr., Reggie Jackson, Hughie Jennings, Tommy LaSorda (Manager), Effa Manley (Executive), Christy Mathewson, Joe McCarthy (Manager), Bill McKechnie (Manager), Stan Musial, Mike Mussina, Herb Pennock, Mike Piazza, Eddie Plank, Cumberland Posey (Executive), Bruce Sutter, Rube Waddell, Honus Wagner, Bobby Wallace, Ed Walsh, John Ward, and Hack Wilson. Next week the United States of Baseball heads for the warmth of the Caribbean and the Island of Enchantment. Puerto Rico is next.

DJ

United States of Baseball- Georgia

Major League Baseball continues to see a steady stream of players from Georgia. The warm weather for much of the year combined with the Braves dynasty in the 1990’s and early 2000’s created a generation of baseball crazed players and fans. The Peach State has sent 390 players to MLB. The Hall of Fame has welcomed six Georgia natives: Ty Cobb, Josh Gibson, Johnny Mize, Jackie Robinson, Bill Terry, and Frank Thomas. Kevin Brown is the greatest pitcher from the Peach State. His career 68.21 WAR ranks 20th among all state and territory leaders. Ty Cobb is the greatest position player. His career 151.02 WAR is the 4th highest among position players. Brown and Cobb’s combined 219.23 WAR ranks Georgia 9th highest among all states and territories.

Kevin Brown was born in Milledgeville. He played 19 seasons in the Majors for six teams: Texas Rangers (1986, 1988-1994), Baltimore Orioles (1995), Florida Marlins (1996-1997), San Diego Padres (1998), Los Angeles Dodgers (1999-2003), and New York Yankees (2004-2005). On the mound, Brown pitched in 486 Games, making 476 Starts, throwing 72 Complete Games, 17 Shutouts, pitching 3,256.1 Innings, allowing 3,079 Hits, 1,357 Runs, 1,185 Earned Runs, 208 Home Runs, 901 Walks, 2,397 Strikeouts, posting a 211-144 record, 3.28 ERA, 1.222 WHIP, and 127 ERA+. Opposing hitters knew they were in for a rough day with Brown pitching.

Brown’s elite pitching earned him six All Star selections, the 1997 World Series, and two ERA titles (1996 and 2000). He finished sixth in the 1989 National League Rookie of the Year voting. He finished in the top six for Cy Young voting five times (1992- 6th, 1996- 2nd, 1998- 3rd, 1999- 6th, and 2000- 6th). He threw a No Hitter against the Giants in 1997. A year later, Brown’s success on the mound saw him rewarded with the then largest contract in MLB history. He signed a seven year free agent contract with the Dodgers for $105 million. It was baseball’s first $100+ million contract. He appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2011. He received 2.1% of the vote, failing to reach the minimum 5% to remain on the ballot.

Unquestionably, Brown’s best season was in 1996 with the Florida Marlins. In 32 Starts, he threw 5 Complete Games, including 3 Shutouts, pitched 233 Innings, allowed 187 Hits, 60 Runs, 49 Earned Runs, 8 Home Runs, 33 Walks, 159 Strikeouts, posted a 17-11 record, 1.89 ERA, 0.944 WHIP, and 215 ERA+. Brown led the National League in ERA, WHIP, and ERA+. He was an All Star, finished second for the Cy Young award, and 22nd for the MVP. Kevin Brown was outstanding and was among the National League’s best in 1996.

No player was ever more fanatical about baseball than Ty Cobb. He was born in Narrows and played 24 seasons for the Detroit Tigers (1905-1926) and Philadelphia Athletics (1927-1928). In 3,034 career Games he collected 4,189 Hits, 724 Doubles, 295 Triples, 117 Home Runs, 1,944 RBI, scored 2,245 Runs, 897 Stolen Bases, 1,249 Walks, 680 Strikeouts, .366 BA, .433 OBP, .512 SLG, .944 OPS, 168 OPS+, and 5,854 Total Bases. When he retired, Cobb held the record for most Hits, Stolen Bases, and BA. Both Hits and Stolen Bases have since been surpassed, but his record .366 BA seems untouchable.

Cobb is perhaps the greatest hitter of all time. He hit over .400 three times. He won 12 Batting Titles in 13 seasons, including nine straight. He led the American League in Hits eight times and collected at least 200 Hits nine times. He led the league in Doubles three times. He hit at least 30 Doubles in 15 seasons and at least 40 Doubles in four seasons. Cobb led the league in Triples four times, legging out at least 10 Triples in 17 seasons, and at least 20 in four seasons. He had seven 100 RBI seasons, leading the American League four times. He led the Junior Circuit in Stolen Bases six times with nine seasons of at least 50 Steals. Cobb was the premier player of his era, winning the 1909 Triple Crown (9 HR, 107 RBI, .377 BA). In 1936, the Baseball Hall of Fame announced its first class: Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Ty Cobb. It was Cobb, not Ruth, who received the most votes, with 98.2% for induction into Cooperstown.

Selecting the greatest individual season of Cobb’s career is nearly impossible. He was consistently brilliant. Examining his MVP 1911 season with the Tigers seems the most appropriate. In 146 Games, he collected 248 Hits, 47 Doubles, 24 Triples, 8 Home Runs, 127 RBI, scored 148 Runs, 83 Stolen Bases, 44 Walks, 42 Strikeouts, .419 BA, .466 OBP, .620 SLG, 1.086 OPS, 196 OPS+, and 367 Total Bases. Cobb led the league in Runs scored, Hits, Doubles, Triples, RBI, Stolen Bases, BA, SLG, OPS, OPS+, and Total Bases. He won the first American League MVP award. He finished 7th in 1912, 20th in 1913, and 14th in 1914 after which the award was discontinued. The MVP returned to the Junior Circuit in 1922, but previous winners were ineligible to win again. It is not difficult to imagine the Georgia Peach winning at least five MVP awards if he was eligible.

Georgia continues to send great players to the Majors every year. The state shows no sign of slowing down. Next week the United States of Baseball goes west, really far west to the Land of the Chamorro. Guam is next.

DJ

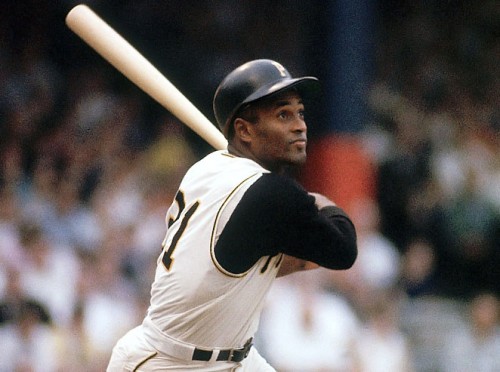

Artistry with a Bat: Roberto Clemente’s Four Batting Titles

Roberto Clemente was many things on a baseball field. A tremendous outfielder, outstanding leader, and natural born hitter. Despite his career being tragically cut short, only nine players have won more Batting Titles than Clemente’s four. It is a testament to Clemente’s skill with the bat.

The nine players out of nearly 20,000 players in Major League history to win more batting titles than the Great One are all in the Hall of Fame. Ty Cobb leads with 12 Batting Titles, a record unlikely to be equaled or broken. Tony Gwynn and Honus Wagner are tied for second with 8 titles. Rod Carew, Rogers Hornsby, and Stan Musial each collected 7. Ted Williams won 6 despite two pauses in his career for military service. Wade Boggs and Dan Brouthers won 5 titles. Clemente is tied with Cap Anson, Miguel Cabrera, Harry Heilmann, and Bill Madlock with four Batting Titles. Anson and Heilmann are in the Hall of Fame. Cabrera will join them when his career is over. Surprisingly, Madlock did not receive the minimum 5% in 1993, falling off the ballot in his first year of eligibility.

Winning multiple Batting Titles in your career is an impressive accomplishment. Clemente won his four titles in the span of seven seasons. He won his first Batting Title in 1961. In 146 Games, Clemente collected 201 Hits, 30 Doubles, 10 Triples, 23 Home Runs, drew 35 Walks with just 59 Strikeouts. He posted a .351 BA, .390 OBP, .559 SLG, .949 OPS, and 150 OPS+. Clemente was named to both All Star games that summer and finished fourth in the MVP voting. The 26 year old could not save Pittsburgh however, as the Pirates finished in 6th place, 75-79. While the team struggled, Clemente began his ascent to super stardom.

After two “down” seasons where he hit a mere .316, Clemente claimed his second Batting Title in 1964. Named an All Star for the fifth consecutive season, he played 155 Games, collected 211 Hits, 40 Doubles, 7 Triples, 12 Home Runs, with 51 Walks and 87 Strikeouts on his way to a .339 BA, .388 OBP, .484 SLG, .872 OPS, and 146 OPS+. Clemente led the National League in Hits, with career highs in Hits (211) and Doubles (40). The 29 year old finished ninth in MVP voting as the Pirates again struggled to a 6th place finish, 80-82.

Clemente won his second consecutive, and third overall, Batting Title in 1965. He played 152 Games, collected 194 Hits, 21 Doubles, 14 Triples, 10 Home Runs, with 43 Walks and 78 Strikeouts. He posted a .329 BA, .378 OBP, .463 SLG, .842 OPS, and 136 OPS+. His 194 Hits and .329 BA were the lowest of his four Batting Titles, while his 14 Triples were a career high. Once again Clemente finished in the top ten for the MVP, 8th. Pittsburgh played their first meaningful baseball late in the season since 1960, finishing third, 90-72.

1966 was another “down year” for Clemente’s Batting Average, dipping to .317, tied for fourth highest in the National League. Ultimately he traded a third consecutive Batting Title for the MVP award. In 1967 Clemente unsuccessfully defended his MVP award, finishing third. His Batting Average rebounded as he won his fourth and final Batting Title. In 147 Games, he collected 209 Hits, 26 Doubles, 10 Triples, and 23 Home Runs, drew 41 Walks with 103 Strikeouts. He posted a career high .357 BA, with a .400 OBP, .554 SLG, .954 OPS, and 171 OPS+. Clemente led the league in Hits for a second time. Despite his efforts the Pirates were a .500 team, 81-81, 6th in the National League.

Any player can have a great season, only elite players can maintain this level of play season after season. In his four Batting Title winning seasons Clemente averaged 150 Games played, 204 Hits, 29 Doubles, 10 Triples, 17 Home Runs, 43 Walks, 82 Strikeouts, .344 BA, .389 OBP, .514 SLG, and .903 OPS. This was the average. These four seasons gave Clemente roughly a quarter of his career Hits (815 of 3,000), Doubles (117 of 440), Triples (41 of 166), and Home Runs (68 of 240), as he hit .027 above his career .317 BA. Every player peaks, but Clemente peaked higher than Everest.

Clemente did not fade in the twilight of his career. He hit a combined .346 from 1969 to 1971, averaging 214 Hits per 162 Games played. Clemente finished second to Pete Rose for the Batting Title in 1969, just three points short of his fifth title, .348 to .345. Clemente played just 108 games in 1970, failing to qualify for the Batting Title. However, his .352 BA would have placed second behind Rico Carty’s .366, well ahead of Manny Sanguillen and Joe Torre’s .325. In 1971, Clemente hit .341 and finished fourth in the Batting Title. The 36 year year old could still hit. His Batting Average in each season from 1969 to 1971 was higher than his Batting Title winning Batting Averages in 1964 and 1965. Clemente remained among the best hitters in the league.

Only a select few are naturally gifted to hit a baseball and without a doubt Roberto Clemente was one of them. His abilities should be celebrated in the same breath as Aaron, Ruth, Cobb, Musial, and Williams. His number 21 should be retired across baseball for his accomplishments on the field and for what he meant to the game off the field. He was a true humanitarian and remains the icon for Puerto Rican and Caribbean players. Retire #21.

DJ

Insanity

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again while expecting different results. The baseball definition of insanity is the Hall of Fame election. Not every player earns a plaque in Cooperstown, but some deserving players have been denied their day in the sun by the current system. Chiefly among those denied their crowning moment are Dick Allen, who died Monday, and Ron Santo. Allen could be voted into the Hall next year. This same cruel fate saw Santo elected to Cooperstown one year after he died. A player does not become a Hall of Famer when they die, let them enjoy their moment.

Debates about a player’s enshrinement never end. Allen, like Santo before his election, is among Cooperstown’s most glaring oversights. The issue is not their statistics, but the system through which players must pass to have their day in the sun. The current system has the BBWAA (Baseball Writers’ Association of America) vote for no more than 10 players appearing on the ballot. The players must have played for 10 years and be retired for 5 years. Once on the ballot, the player has up to 10 years to receive the necessary 75% of the vote for enshrinement. They must receive at least 5% to remain on the ballot each year. If a player is not elected through the BBWAA they can appear on the Veterans Committee ballot 20 years after they retired.

Limiting players to 10 years on the ballot ensures steady turnover. The same with the minimum 5% rule. The issue is the maximum of 10 rule. This rule needs to be expanded, potentially with no maximum. Allowing no more than 10 players to receive votes hurts non-first ballot Hall of Famers. Ken Griffey Jr. was a lock for Cooperstown, but Larry Walker needed the full 10 years on the ballot. Raising the number of votes would have had Walker elected sooner, thus creating space for other worthy candidates. Players like Omar Vizquel, Dale Murphy, Scott Rolen, and Andruw Jones.

The Hall of Fame voting process has not allowed Cooperstown to grow with the game. Expansion has not seen an equal growth in the number of Hall of Fame inductees. The watering down of baseball has not happened, instead more fans are engaged and more players reach the highest level of the game.

Cooperstown inducted its first class in 1936. Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Babe Ruth, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson are the original five. Since the original five, the BBWAA has elected 127 players. The Veterans Committee was established in 1953 to give players a second look to ensure every deserving player makes it to Cooperstown.

Since 1953 the BBWAA and the Veterans Committee have mirrored each other in sending players to the Hall. The BBWAA has elected 104 players and the Veterans Committee has elected 84. Players are not elected every year. An average of 1.89 players have been elected in the 55 years the BBWAA has elected players. The Veterans Committee has averaged 1.83 players a year in the 46 years they have elected players. These totals do not include Negro Leagues players, as the Hall of Fame has a separate committee focused on their election, or managers and other non-players who have their own path to Cooperstown. In the decades since the establishment of the Veterans Committee the average number of players elected to the Hall are as follows: 1960s (1.50 BBWAA vs 2.25 Veterans), 1970s (1.44 vs 2.20), 1980s (1.80 vs 1.33), 1990s (1.67 vs 1.87), 2000s (1.70 vs 1.67), and 2010s (2.67 vs 1.50). The difference between the BBWAA and Veterans Committee in the 2010s was not a decline by the Veterans Committee, but an increase by the BBWAA. Perhaps the BBWAA voters are changing their views on what a Hall of Fame player is, but for many the change is too slow or too late.

Far too many players are entering the Hall through the Veterans Committee. The understanding of the game changes over time, giving the Veterans Committee a greater ability to consider each candidate. However, significantly more players should be elected through the BBWAA than the Veterans Committee. The second look at a player should see only a few players elected. When the numbers entering the Hall are so similar, it is clear the BBWAA voting process needs adjusting. The Veterans Committee should be the last resort, not the path for 45% of Hall of Famers since 1953. The BBWAA should do the heavy lifting by expanding voting. 10 votes is not always enough for the candidates on the ballot. The worry is undeserving players will become Hall of Famers, but the reality is deserving players are being excluded. Dick Allen and Ron Santo did not live long enough to have their day in the sun. They both deserved enshrinement in their lifetimes. Honor the game and the people who dedicated themselves to it, it is past time to change the Hall of Fame voting process.

DJ

Tip of the Cap

100 years since the founding of the Negro Leagues. 100 years of progress in baseball and America. 100 years and the United States is still facing some of the same issues that unjustly kept African-American players out of Major League Baseball for decades. 100 years ago African-Americans just wanted a place to play baseball. Rube Foster made the dream of professional baseball a reality when he founded the Negro National League in Kansas City in 1920. Every lover of baseball is forever indebted to him and everyone in the Negro Leagues who played the game they love under difficult conditions. Long bus rides, segregated hotels and restaurants, and racism were part of daily life for a Negro Leagues player. Despite all the hardships, legends emerged. Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, Oscar Charleston, Martin Dihigo, Turkey Stearnes, and countless others. Their greatness was recorded in stories more than statistics. The comparisons to the legends of Major League Baseball like Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Cy Young, Honus Wagner, and others can never be settled. It is an American tragedy that racism prevented these legends from playing with and against one another. The talent in the Negro Leagues was undeniable, yet far too much has been lost to history. Preserving the history and legend of the Negro Leagues is essential in telling the history of baseball and America.

Derek tipping his cap to the Negro Leagues with his Detroit Stars cap. (The Winning Run/DJ)

Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, has invigorated the attention and drawn the respect the Negro Leagues, and its players, deserves. His passion for the Negro Leagues has helped spotlight the players and teams that paved the way for African-American baseball. The 100th Anniversary of the founding of the Negro National League is being commemorated with a simple campaign, a tip of the cap. More could be done, but the Covid Pandemic has all but halted public gatherings. We can never fully repay the Negro League players for everything they gave to baseball and the country, while enduring untold hardships. We must honor their experience and work to create a just world, free of racism, on and off the diamond. We salute the Negro Leagues and the men and women who loved baseball and refused to let racism stand between them and the game they love.

We humbly tip our caps to the Negro Leagues.

Bernie tipping his World Series champion Washington Nationals cap to the Negro Leagues as the Fantasy Baseball trophy looks on in the background. (The Winning Run/BL)

Jesse tipping his Gwinnett Stripes cap to the Negro Leagues. (The Winning Run/JJ)

DJ, JJ, & BL

Missed Opportunity

Growing up around Atlanta in the 1990’s there was plenty of great baseball games and players to watch. Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, Tom Glavine, and Chipper Jones were all Hall of Fame players. Andruw Jones, Otis Nixon, Javy Lopez, and so many more were great players to watch. These riches on the diamond were amazing, but as time has gone by the realization of how great it was to watch these players night after night has set in. Fans across the country might only have a few chances each season to see these players and they understood that you should take the time to slow down and appreciate them.

The understanding that I need to slow down and watch when a great player passes through town has sunk in more as I get older. Appreciating the greatest of a player goes beyond the highlight reel plays. It is watching how they approach each pitch throughout a game, both at the plate and in the field. There are only a select few players in baseball that can capture my attention even when they are not making great plays. Players who make me stop and watch just in case they do something amazing.

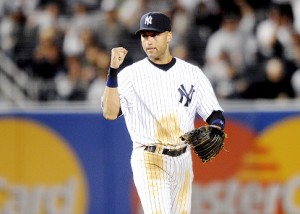

These stop what you are doing and watch players are the elite few. Some I have had the pleasure of watching in person, others I missed my opportunity to watch their greatness. When I was living in New York for graduate school and the few years after, I was lucky enough to see Derek Jeter play on a few occasions. Jeter was never the best hitter, but he was good one. He did not have the most power, the biggest arm, or greatest fielding range, but he commanded everything inside Yankee Stadium. While only getting to see Jeter in the later part of his career, it was still special to see one of the few players who was respected across baseball without exception. It takes a special player to be respected by Red Sox fans even though he was a lifelong Yankee that broke Boston’s heart on so many occasions. Watching Jeter play consumed a majority of my time at Yankee Stadium. I watched how he moved with every pitch and how he was the man on the field and yet everyone knew in their heart that he was never the most talented. Derek Jeter could do everything on a baseball diamond, but it was what did not show up in the box score, which set him apart from everyone else.

I usually went to Mets games simply because the tickets were cheaper, however when I did venture up to the Bronx and Yankee Stadium it was special. Even inside the new Yankee Stadium the history of the Yankees resonates. Watching two players who will and should be first ballot Hall of Famers, Jeter and Ichiro, plus my favorite player in Andruw Jones meant the 2012 Yankees were the best for me. Watching Jones patrol the outfield with the Braves growing up spoiled me. If it was catchable, he seemed to always catch it. The 2012 Yankees meant I got to relieve a bit of my childhood with Andruw Jones, watch the coolest man in baseball in Derek Jeter, and watch one of the greatest pure hitters of all time in Ichiro.

The beauty of Ichiro’s swing and his athleticism at the plate are what always caught my eye. He seemed, and still seems, like a magician at the plate. He never seems to be fooled on a pitch; he might swing and miss but never look awful in doing it. Ichiro is to me what a baseball player ought to be. He can beat you with power, though he rarely displays it. He can put the ball in play and then beat you with his speed. Then on defense, he can chase down fly balls with the best of them. If runners are on base they advance at their own risk, as Ichiro is blessed with a cannon for an arm. Ichiro has all five tools, though he keeps his power hidden until it is absolutely necessary. Watching Ichiro hit is the closest I will ever come to watching a hitter on the same level like a Ted Williams, Ty Cobb, Joe DiMaggio, or Honus Wagner. Watching Ichiro and Jeter play were and are a return to my childhood. A return to when baseball was simple and the players were larger than life; the baseball that was and forever will be my first love.

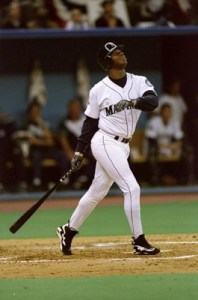

I have not gotten to see every player I wanted to see play in person, though I did on television. The two biggest players that I did not get to see play in person that I will forever be sad about are Ken Griffey Jr. and Vladimir Guerrero. Yes, I saw both players on television, but not in person. There is a big difference in appreciating how great a player is when you see them not through a camera lens, but with your own eyes.

Ken Griffey Jr. was the coolest man on the diamond plus he had the sweetest swing in the game. (www.tapiture.com)

The two most obvious reasons I never saw Ken Griffey Jr. play in person are that he played in Seattle and Cincinnati and I lived in Atlanta. This meant at best his team would come to Atlanta once a year. Interleague play did not start until 1997. This meant seven seasons of Griffey’s 22-year career were already gone. Then there were the last three years in Seattle before he moved on to the Cincinnati Reds. There were some opportunities to see Griffey play in Atlanta during interleague at some point with the Mariners, but I went to only two or three games a year growing up. So not great odds, plus we usually went to the less popular games with the slightly cheaper tickets and the smaller crowds. I loved going to games, but looking back, I wish I had seen Griffey. His time with the Reds meant he only came to town one time a season, and sadly there were several lost seasons in Cincinnati due to injuries. Griffey was, and remains, the prototype for what it means to be cool on a baseball field. Jeter was New York cool, suave. Griffey was fun, exciting, and electric. His wiggling batting stance is still mimicked by people today, though admittedly no one else, even in softball leagues can ever hope to hit a ball like he did. Griffey could amaze you and do things that just did not make sense for a player his size. You expected Frank Thomas and Albert Belle to hit the ball a mile, but Griffey at worst hit the ball as far as they did, plus he could run like the wind. Ken Griffey Jr. was a once every few generations type player and I missed him. As great as his highlight reel is, I can only imagine how great it would have been to see him play in person.

Missing several opportunities to see Ken Griffey Jr. makes sense, not seeing Vladimir Guerrero play does not. Guerrero spent 8 of his 16 seasons with the Montreal Expos. Playing in the National League East with the Braves meant I had plenty of opportunities to watch him play, but for whatever reason I never did. It was not from a lack of interest, I just never seemed to go to Turner Field when the Expos were in town. Not sure why, just the way it worked out. Guerrero was a lot like Andruw Jones, great power and speed and a howitzer for an arm. The main difference between Guerrero and Jones was that Guerrero was a more complete hitter and Jones played for Atlanta, not against them. Vladimir Guerrero never met a pitch he could not hit. It reminded me of playing baseball in the street with my brother and friends. If it was within reach, you swung, partly so you did not have to go pick it up and partly because it may be the best pitch you will see. Guerrero never seemed to care if the pitch was a foot outside and head high, he could serve it into the outfield. He could also bloop a ball into short left field after the pitch bounced in front of the plate. Ichiro is a magician in the batter’s box in the sense that he can almost place where he hits the ball. Guerrero is a difference sort of magician as he can hit nearly everything thrown towards the plate, and hit it well. The other thing I missed was seeing Guerrero unleash his arm. There are few players with arms that stop the opponent from even attempting to take an extra base; Rick Ankiel and Jeff Francoeur are the players in recent years that come to mind regarding the fear their arms put into the minds of opposing base runners. Perhaps Vladimir Guerrero was not the best player in terms of doing the conventional things on a diamond the best, though he did them extremely well. What I missed the most in not seeing Guerrero play in person is his ability to leave fans speechless. He could hit or throw a baseball a mile, or single on a pitch that most players could not even reach. Vladimir Guerrero took the sort of baseball that I grew up playing to the Major Leagues and still made it look as amazing as it felt.

Vladimir Guerrero never met a pitch he could not hit or a runner he could not throw out. (www.prosportsblogging.com)

The opportunity to see something unique and amazing at a baseball game exists every time the gates open. You could see Matt Cain throw a Perfect Game (as Jesse did in San Francisco), watch the final game at old Yankee Stadium (as John, Jesse, and I did in 2008), or just see a fun game like I have on so many occasions. Baseball is a team sport played by individuals. These individuals are what make the game great. Players of all size can find success on a baseball diamond, whether they are Jose Altuve at 5’6”, Randy Johnson at 6’10”, or Jonathan Broxton at 300 lbs. Great players come in every physical form possible and they are all capable to doing something amazing. Most of us do not have the financial ability to go to every game, but we should all make the time when these elite, once in a generation type players come to town. Continuing to put off going to see Mike Trout, Bryce Harper, Andrew McCutchen, Aroldis Chapman, and others will be a sad memory. There is no guarantee they will do something amazing at the game you attend, but you will still be able to say you saw them play. No one cares if the one game you saw Sandy Koufax pitch he did not win the game, you still got to see Koufax pitch. Do not miss your opportunity to see great players in person. We can all watch highlight reels, but watching in person is always special and you will remember it better than any video.

DJ

Knowledge is Power

The Unforgettable Season by G.H. Fleming

1908 was a great year for baseball. It was more than just the most recent World Series title for the Chicago Cubs. The season was one of the most exciting pennant races in baseball history. The Chicago Cubs, the New York Giants, and Pittsburgh Pirates fought each other from Opening Day throughout the season until the final day of the season. Hall of Famers Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner, Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, (Joe) Tinker-to-(Johnny) Evers-to-(Frank) Chance, John McGraw played prominent roles throughout the season.

The excitement of the pennant race is retold through newspaper articles that were published during the great 1908 season in The Unforgettable Season by G.H. Fleming. This approach to the retelling of the pennant race allows the reader to be transported back in time. The use of the newspaper articles prevents the book from taking on too much of an academic tone, but rather it exudes the storytelling of every man. Fleming only inserts necessary background information, which helps to bridge the gap over the years and prevents any information from going by without understood. The daily notes regarding the previous day’s action show the dominance of the Pirates, Cubs, and Giants over the rest of the National League. The ebb and flow of these three great teams only built the tension and excitement of the season the closer it drew to October.

The most infamous play of the 1908 season surrounded the actions of Fred Merkle. While I knew the story of Merkle prior to reading The Unforgettable Season, Fleming allows the newspapers to paint a much clearer picture of the man prior to his gaining infamy. This clearer picture of what he could have become as a player before the newspapers and fans used him as a scapegoat for why the Giants did not reach the World Series. (Keith Olbermann of ESPN recounts Merkle’s story well).

Fleming does an excellent job of stay out of the way of history. He allows the story to tell itself. This is a refreshing approach, as it would be easy for any author to unintentionally get into the middle of the story. Modern day analysis of the season could shed more light on the details of the 1908 season. However, I believe Fleming was smart to simply stay out of the way of the history. The Unforgettable Season provides a glimpse of how great a pennant race can be, however the pennant race is not the same as it once was as the playoffs have expanded beyond just the World Series. The expanded playoffs are not better or worse, just different. The expanded playoffs allow more teams and fans to stay engaged in the baseball season later in the season than they might otherwise. Fleming provides an excellent read for anyone who wants to gain a greater understanding of baseball and its history.

DJ

More from The Winning Run library.

Long winters without baseball are awful. However, one of the best ways to keep your love of the game alive and well is by reading baseball. My library has plenty and I wanted to share a few with you.

The Mick (1985) by Mickey Mantle and Herb Gluck

One of Mickey Mantle’s many biographies. In The Mick you get a view of his life during his career but not so much on the field. He talks about teammates, parties, his family, and career moments. You get a feel for his love of the game, but also the hatred of things that occurred in his career. It is an enjoyable and quick read.

Faithful (2005) by Stewart O’Nan and Stephen King

Yes this one is about the Red Sox and their championship season in 2004. Yes it was painful to read (as the resident Yankee fan). Despite this, authors Stewart O’Nan and Stephen King make you keep reading as they chronicle the Red Sox through email and blog posts and their knowledge. They are true friends and true fans of baseball. They remind me of my two partners in this blog and their knowledge and passion. This is a great read and a great part of history.

A chronicling of Joe DiMaggio’s record 56 game hitting streak. This is a great book about DiMaggio’s life to that point and what he went through during that time. It looks into what pressures and stress, and how DiMaggio dealt with them, his family, and teammates. Books like 56 help to show the personal side to these legends we will never be able to meet in real life.

Moneyball (2004) by Michael Lewis

Why haven’t you read this? The movie is great, and the book is amazing. I didn’t want to even put it here but figured it deserved recognition. Read this or you will never get on base.

JB

The Lost Art of the Triple

The most exciting play in baseball is the triple. Rarely is a triple a forgone conclusion. Usually it is a crazy dash around the bases, while the fans and teammates yell for the batter to run faster and to either stop at second base or to slide into third. A triple suddenly changes the complexion of an inning and of a game. The pitcher can be sailing along and with one pitch can go from relaxed and pitching from the wind up to having a distraction on third who makes you shorten your windup from the stretch. The triple is a game changer.

The way that baseball is played and how fields are laid out has reduced the triple to an rarity. The home run has replaced the triple as the means of pushing across multiple runners with one swing and changing the fortunes of a team. The triple has become a lost art. The game changes as time passes, different strategies and approaches are adopted. Pitchers no longer are expected to pitch complete games nearly ever time they take the mound. Instead pitching into the 7th inning is considered a good outing. Batters no longer content to hit singles and then rely on stolen bases or the hit and run to get them around the bases. Baseball changes and different aspects of the game change. Unfortunately the triple has become less of a weapon used by teams, and it has reduced the prevalence of the most exciting play in baseball.

Understanding how baseball has changed and how the triple has become less and less utilized you simply need to look at how modern players stack up against players from baseball’s past. Sam Crawford holds the record for most career triples with 309. The remaining of the top 5 in career triples are Ty Cobb with 295, Honus Wagner with 252, Jake Beckley with 244, and Roger Connor with 233. The active leader in triples in Carl Crawford with 117 triples, this is good enough for 103rd all time. Crawford is at best on the back side of his prime, and at worst he is on the back side of his career as a whole. Rounding out the top 5 among the active leaders for career triples are Jose Reyes with 111 triples, he ranks 123rd all time. Jimmy Rollins has 107 triples which is good enough for 138th all time. Juan Pierre is fourth among active players with 94 triples, he is 189th all time. Rounding out the top 5 of active players with career triples is Ichiro Suzuki with 83, which has him with the 256th most career triples. None of these players have much of a chance to threaten the career record. Age and time will eventually catch up to all of them, thus protecting Sam Crawford and his record. It is easy to argue the career triples record is safer than nearly every baseball record, including Joe DiMaggio‘s 56 game hit streak.

The difficulty of the career record may be out of reach due to the changing of how baseball is played. However reaching the top 5 for most triples in a season is more attainable, although breaking the single season record maybe completely out of reach. Chief Wilson holds the single season triple record with 36 in 1912. David Orr is tied for second with 31 triples in 1886, which was tied by Heine Reitz in 1894. Perry Werden hit 29 triples in 1893. Rounding out the top 5 for most triples in a single season are Harry Davis in 1897 and Sam Thompson in 1894 with 28 triples. The heyday of the triple was during the dead ball era, and there have been only a few players who have had even a single season with a high number of triples. They have become more and more rare as time has passed. Since 1994 only four players have had a single single where they hit 20 or more triples: Curtis Granderson with 23 triples in 2007, Lance Johnson with 21 triples in 1996, Christian Guzman with 20 triples in 2000, and Jimmy Rollins with 20 triples in 2007.

Baseball fans should appreciate the players who can round the bases at top speed to go from batter to 90 feet away from scoring. The triple has become a rare event in baseball and it should be treasured when it does happen. The changing of the game has protected Sam Crawford’s and Chief Wilson’s records from being broken. While I personally love seeing triples, the evolution of baseball is good for the game as it continually reinvents itself. The premium placed on power in today’s game will mean the triple will become less common. Players are bigger and stronger, which usually means they are not nearly as fast. This reduction of speed means there will be plenty of doubles and home runs, but the triple and stolen base will be a little less common and when they are used they should excite fans and players even more.

The triple is becoming a lost art. While it is unfortunate that part of baseball’s history is becoming more and more rare, it is just part of the evolution of the game. The triple may be a thing of the past, it still has a place in the modern game. Playing small ball will never go out of style, and because of that the triple will remain an exciting part of baseball forever. The triple is not completely lost, it is just in the background and shows itself on occasion, and when it does it will ignite baseball fans everywhere.

D